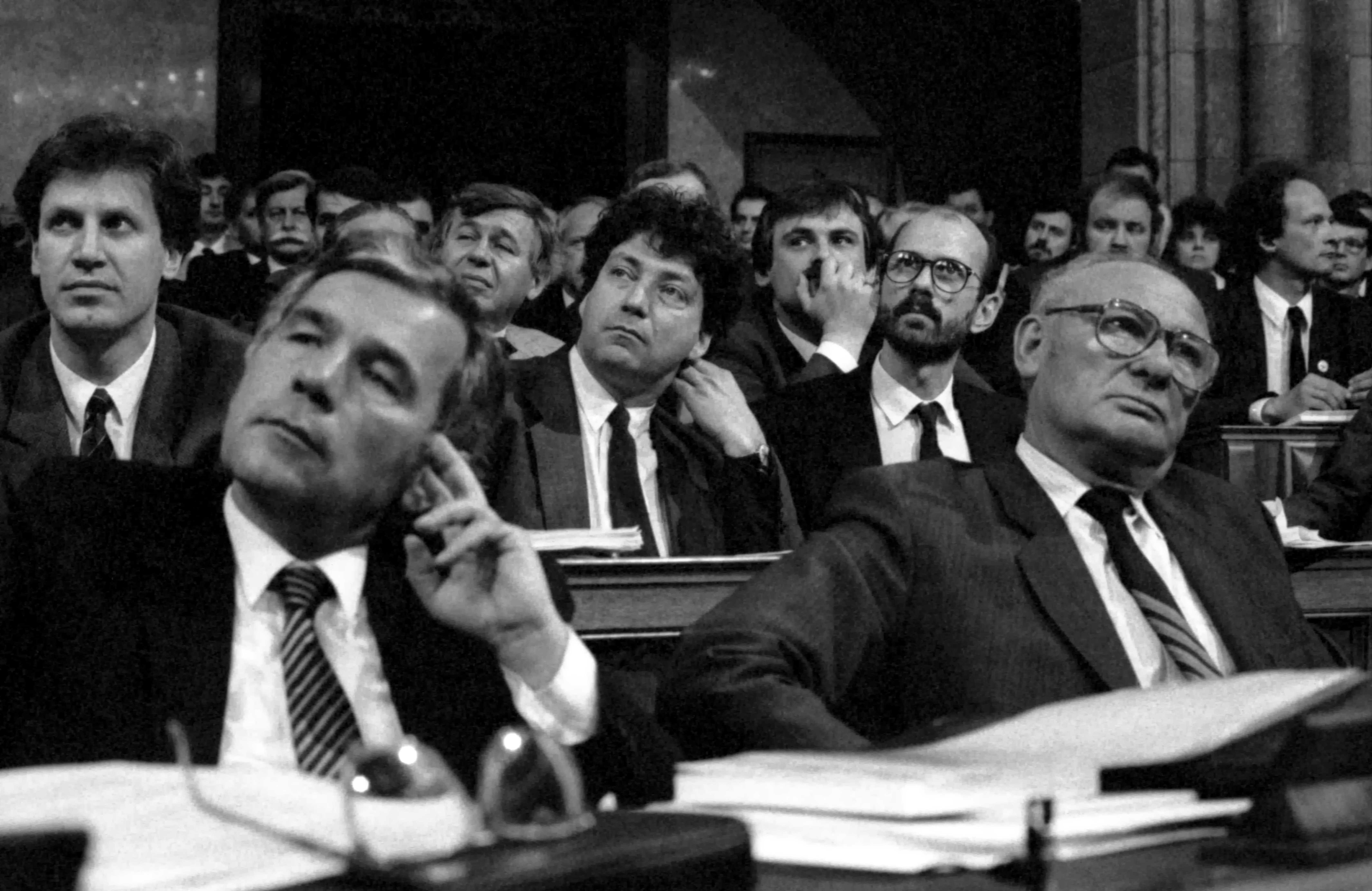

Piroska Nagy’s Photos of Hungary 1988-1990

The next demonstration was held on March 15, 1988. I decided to take along the half-automatic Minolta I had received from my mother as a graduation gift with me. While my sister taped the speeches on a tape recorder, I took pictures. People were making history, and I felt that I had to document what was going on. – Piroska Nagy

US traveling photo exhibit

October 3 – October 21, 2014

Organized by the Central European California Cultural Initiative, 56 Films, and Lauer Learning

Exhibit Director:

Réka Pigniczky (CECACI, 56Films) reka@56films.com, tel: 510-566-6715

Coordinator:

Andrea Novák (Körösi Csoma Sándor intern, San Francisco) novakandrea@yahoo.com

Project Description

“A Witness to Change” is a traveling photo exhibit in the U.S. during the month of October, 2014. The photos, taken by American-Hungarian Piroska Nagy between 1988 and 1990 are a compelling documentation of Hungary’s transition to democracy. 30 of Piroska’s best photos from 1988-1990 will go on exhibit in seven U.S. cities as part of local commemorations of the 25th anniversary of the fall of communism. Piroska will be present at each opening and give a talk, to be followed by a Q &A, of about her photos and the events of the transition in Hungary.

The cities included in the tour will be Atlanta, Chicago, San Francisco, Seattle, Denver, Cleveland and Washington, D.C. The cities were chosen in part to include some cities where there is less frequent Hungarian-American activity, in order to facilitate the commemoration of the transition to democracy 25 years ago.

Proposed dates

Atlanta: 10/3, 10/4

Chicago: 10/7

San Francisco: 10/10, 10/11

Seattle, WA: 10/12

Denver: 10/16

Cleveland: 10/18, 10/19

DC: 10/21

Background

Piroska Nagy, born in the United States to parents who fled Hungary after the revolution of 1956, moved to Hungary in 1980 to study at the Eotvos Lorand University in Budapest. Her father, the late Dr. Karoly Nagy, a participant in the revolution and later the founder of the Hungarian school in New Brunswick, New Jersey and an active member of the Hungarian-American diaspora, encouraged Piroska to observe and to take part in the changes going on around her in Hungary. Piroska did more that that: she ended up documenting Hungary’s transition to democracy over the span of three years. Her photos show courage, creativity, and a real civic involvement in the events that brought an end to nearly 40 years of dictatorship under the Soviet system.

Her photos were published in Western and Samizdat publications between 1988-90 and since then have been included in various online collections, including that of the 1956 Institute in Budapest. The photos have also been published in a book by the prestigious Kieselbach Gallery entitled, “Years of Euphoria, 1988-1990.”

In describing Piroska’s work, Janos M. Rainer, the head of the 1956 Institute, writes: “Her determination to document is characteristically the decision of a private individual made out of civil courage due to the absence of freedom of the press and publicity. She does not allow the officials – them – to immortalize the events and participants, does not want their iconography to define the contours of the character of 1989. She strives to inform, to provide an authentically civilian report of what is happening. Even she herself, the characteristic figure of Piroska Nagy the photographer, became one of the emblems of the civil actions of 1988-1990.”

Piroska took her last picture documenting the transition in 1990, after the first official session of the new, democratic parliament. She now teaches Hungarian culture and the history of communism in the region and especially Hungary to foreign students at the American International School of Budapest. She is an engaging and inspiring speaker, an authentic witness to the changes that occurred in Hungary 25 years ago.

She writes of her photography, “The next demonstration was held on March 15, 1988. I decided to take along the half-automatic Minolta I had received from my mother as a graduation gift with me. While my sister taped the speeches on a tape recorder, I took pictures. People were making history, and I felt that I had to document what was going on. (…) From then on I felt it was my duty, my moral obligation, to document the activities of the opposition. I had much less to lose than they did. I was an American citizen. The worst thing that could happen to me was to be expelled from the country, at least so I thought.”